Those called by their names

MEMORIAL

At Budapest’s Eötvös Lóránd Universtiy a holocaust memorial for former teachers and students has been inaugurated. 200 meters, 198 names, 9454 characters.

| Laborczi Dóra |

2014-12-02 08:00 |

I’m standing in the crowd in the university’s Trefort garden and looking for the monument. During the speeches, I am trying to spot the black veil or where the memorial plaque is.

Some photographers are shooting pictures of the wall. I am looking at the bricks, but see nothing, although I’m trying hard. The monument is nowhere, I give it up, I try to listen to the speakers.

Tamás Dezső, the 204. Dean of the University, apologises to those whose lives were, although under political pressure, ruined by his predecessors’ measures. To those whose names have not been mentioned too often in the last 70 years, because these names remind us of times which would be better to forget.

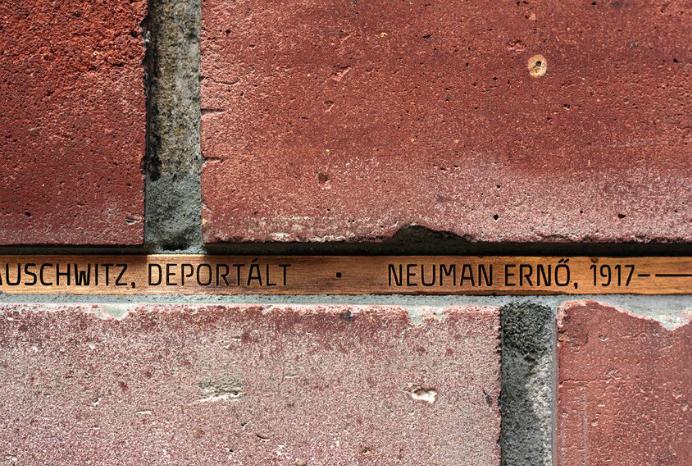

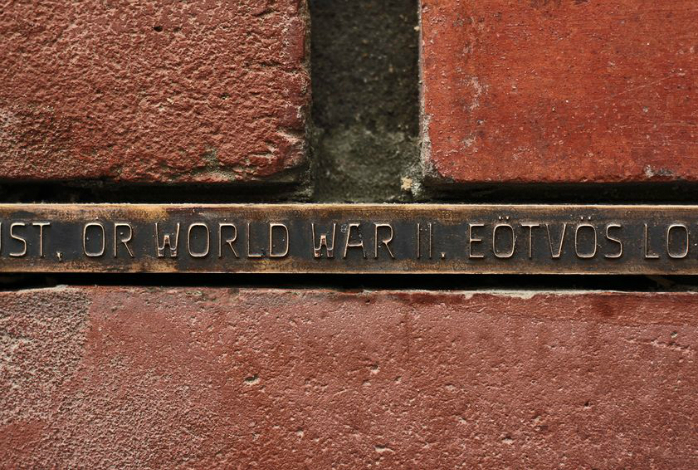

Then the late November sunshine deflects on an almost hidden golden stripe between the bricks in the wall, and now I see in the grout the names of 198 forgotten victims. The horror is linked to names, it is personalised, now there are faces in the mass.

Students are reading out the names and we are quietly progressing along the copper stripe uttering the same names, some quietly, some loudly. Moving along the wall, we are reading the names, dates of disappearance and death. 198 names, 200 metres, 9454 characters. If I wrote all of them here, it would be longer than this article.

The memorial inaugurated at the University’s Faculty of Humanities on 14 November 2014 is the climax of the “Sign in the garden” (Jel a kertben) project, but it is not the beginning and not the end of it. The project linked to it includes research and a conference which will open new roads for the victims’ families, for the present and future students, for the district as well as for the country. The university placed this research and the memorial into a space which is unprecedented in Hungary. And the depth and form of this micro-history is also unique.

“Everything must be written about the unknown.”

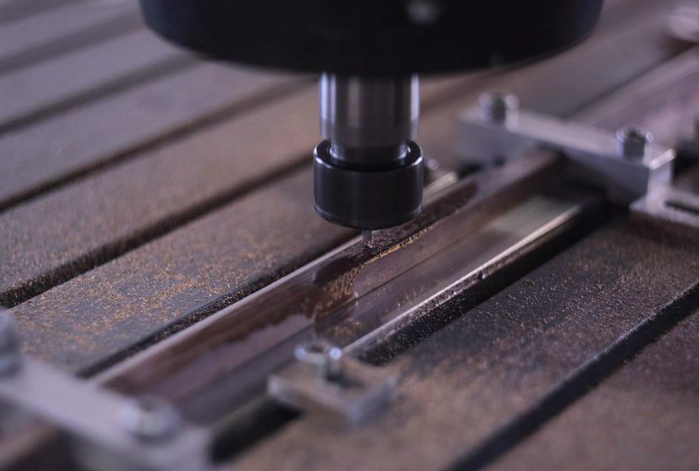

At the beginning of 2014 the university announced a grant which attracted more than 30 gradual and post-gradual students of architecture and their teachers to submit their concepts. At the end of the procedure the “Names in the grout” plan came out the winner.

“It was not our aim to erect another statue, which sinks into oblivion in no time, but we wanted to create something which is not necessarily easy to discover or interpret, but which can raise relevant questions for every generation in every period of time.” says Samu Szeremey, an architect, in an interview.

The memorial is a novelty in the way who it commemorates and how it commemorates them: it is not a monumental statue which is only too easy to get used to it, but a quiet, humble, barely visible and still very touching remembrance.

“The names are put in a random order since they came here to this university together until they died as victims of incomprehensible traumas between 1938 and. 1944. They have now become the university’s loss: this institution always commemorates its famous dead, but the unknowns have only now joined them. It is well-known that Auschwitz is the largest Hungarian cemetery, but many people try to forget this, hence the enormous difference between names without traces and names which have a trace exactly where the people bearing these names actually walked, lived and worked. A website will also be set up: with all the curricula vitae and with a lot of photos. Antal Szerb or Halász Gábor are well-known, so we don’t have to write about them a lot here, but we must write everything about the unknown.” claims Péter György the Head of the Institute for Art Theory and Media Research, who was one of the originators.

Lives which disappeared in oblivion are not easy to be brought back to the surface: a substantial amount of research preceded the planning and implementation, and this research has not ended yet. The research and the conference give a scientific dimension to this project, and it also contributes to building local identities: “you don’t only come here blindly, but you know who lived her and what happened to them. It is only a tiny sign, but it must be visible. Perhaps we will have to lift it and move it closer the light, but it will be there, and it will be visible.” adds Péter György.

Identity shaping affected primarily the students involved in the project, as Flóra Gadó pointed it out during the panel discussion of the conference: “when they reached the stage of working on the actual life stories of the victims, distancing themselves just did not work any more.”

A special personal dimension of the project is that one of the architects involved to implement the plan is János Roth. His father, Pál Roth was one of the victims and his name is now in the wall. “This was tremendous joy and trauma at the same time.” remembers Péter György.

This memorial is not only the excavation of the past, but the personal, the scientific and the artistic are interwoven in it, it is also contemporary architecture appearing in a local, museological space, it is asking questions and offering answer, it is present and past. “This whole thing is and can be because it is as unnoticed as unavoidable. And this is the key question. Stay outside the large, politicised space, this is the solution. And this is the best argument for local museology and for careful addition.” summarises Péter György.