The mummy of a 5-year-old boy

STORY

What do we know about a little boy, Zoltán Arányi, whose mummy is owned by the Semmelweis Museum of Medical Science? Here is something we have found out about him in an exhibition of the Museum of Natural Science.

| Scheffer Krisztina |

2015-04-29 17:52 |

Zoltán Arányi was born on 21 January 1856 in Budapest. He was the son of Lajos Arányi and Johanna Joachim. His mother was born is Köpcsény, which now belongs to Austria and bears the name Kittsee. She was one of the eight children of a family with a long history in trading. In order to ensure better education opportunities for the children, the family moved to Pest in 1833 [a time when Buda and Pest were two separate cities on the opposite banks of the river Danube]. Johanna met János Rechnitz, her first husband, here. They soon had four children. After her husband’s death, Johanna, presumably in 1853, got married to Lajos Arányi, a well-known teacher and doctor, and gave birth to a further five children, out of whom Zoltán was the third.

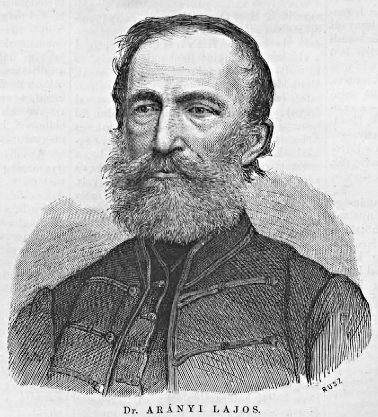

Lajos Arányi (1812–1887) was a medical professor, an archaeologist and one of the outstanding figures of Hungarian cultural history. An offspring of a Transylvanian family, Arányi first studied law and art history, but his attention turned to medical science after the cholera epidemic in 1831. Having finished his studies he became an assistant professor and spent some time at the universities in Vienna and Padua. In Hungary he was the first to see practise autopsy as a branch of science and also wrote a course book on the topic. He was member of the faculty at the University of Medical Science in Budapest for almost 30 years. He financed the first post-mortem lab at the university, performed thousands of post-mortem examinations and created 3500 anatomical specimens. He became a member of the Hungarian Academy of Science in 1858. His son, Zolika, was born 2 years earlier. In his journal he reflected on this:

Monday, 21 January

Monday, 21 January

At half past three in the afternoon my son was born. I had forecasted him, just like I had forecasted Hortenzia. I was not so happy with either Hortenzia or Árpád [the two older children of the family], and I love this little one already as a baby, something I cannot say about my other two children. May God fulfil my prediction that he be a humble and decent man.

Wednesday, 23 January

My son was baptized today and received the names Josef and Zoltán.

However, his hopes did not come true: his son died in 1861 or 1862.

The mourning father, as one of the greatest experts on embalming bodies, wanted to save his son from decay. He used his own method to mummify Zolika’s body, the very same method he applied on the dead bodies of some well-known figures of the era.

Somewhat uncannily he put down the details of the procedure in his diary a week after his son’s birth.

He soaked the body in a special liquid for 100 hours and the separated head in a different one for 12 hours.

Gyula Magyary-Kossa claims that “Arányi was a great artist of embalming and he did not put up with merely injecting the body, but he painted the face and put shells under the eyelids to prevent them from sinking in. The embalming procedure was done so thoroughly that 153 years after his death, Zolika’s body is in very good conditions.

First, and for many years, the little body was sitting next to his father’s desk in his study and when the father followed his son, the family kept the body in the house until 1925.

First, and for many years, the little body was sitting next to his father’s desk in his study and when the father followed his son, the family kept the body in the house until 1925.

Having seen the success of the international health exhibition in Dresden in 1911, the Hungarian government decided to organize a similar exhibition in 1926. The exhibition was titled “The Human” and it offered the opportunity to participate to all kinds of organisations belonging to or dealing with health care.

The exhibition housed in the Industrial Hall in the city park was opened on 29 May 1926 by Miklós Horty, the Governor of Hungary. This was the first time when Zolika’s body was on public display.

After the exhibition the family donated the mummy to the medical university’s Institute for Forensic Science where it remained until 1969 when the newly founded Museum of Medical Science received it. The museum carried out an examination of the body, but at that time a deeper analysis could have only been possible with invasive and destructive methods, which was not undertaken finally. Still very little is known about the technique Arányi used.

Zolika’s body is covered in velvet clothing and white underwear. Under that the body theres is a 5-layer bandage. He is wearing woollen socks and leather shoes. To illustrate how history batters even the dead, one has only to recall the accounts of eyewitnesses: Russian soldiers took Zolika’s trousers during the Second World War, hence the white underwear we see now.

This is the first time since 1926 when visitors of a public museum can see this unique mummy.