Everybody is born a bear

EXHIBITION

Eszter Götz has gone to see the new exhibition in the Museum of Ethnography in order to find out more about the world of summer camps and counter-pedagogy.

| Götz Eszter |

2015-06-10 10:52 |

One of the reassuring lessons history has taught us is that nothing is perfect. Even the totalitarian regimes of the 20th century operated with a certain margin of error: some fields remained unseen and uncontrollable. Such a place was Eszter Leveleki’s summer camp in Bánk, a little village 40 km north-east of Budapest. Today the participants recall these summer weeks as the time of freedom, and after seeing the exhibition one cannot but agree with them.

Eszter Leveleki was a student of Márta Nemesné Müller, a keen follower of Ferenc Mérei and the Montessori pedagogy. Ms. Leveleki announced her summer camp 1938 and promised a cheerful vacation on the camp’s leaflet. By a few summers later it had turned out that the camp is much more than that. She built up a little state on a remote lakeshore, a constitutional monarchy with its rituals, its own language, a museum, the camp Olympics, a newspaper and with laws created by the bears and the witches (that is the boys and girls in the camp). It was a world based on a role play where children could regulate their own life and where the first king was a two-year old toddler called Pipec, sitting on a potty. The summer holiday, a never ending game, quickly became an adventure within safe boundaries. Although only twenty-thirty children came here in two groups every summer, the camp turned out to be surprisingly influential. The children took away with themselves the experience of freedom, equality and independent decision-making into an increasingly authoritarian world. During the period of the anti-Jewish laws, the camp offered protection to those children who were forced to wear the yellow badge, and in the war years it was one of the very few safe places for a Jewish child. In the summer of 1945 Soviet troops transported the children to Szilvásvárad (a small village about 100 km from Budapest), where they were offered a temporary shelter. Communist goodwill wore off quickly and by the early1950s Eszter Leveleki was banned from pedagogical work in schools due to her supposed harmful influence on children, but luckily the camp subsidized by the parents in small and remote Bánk did not attract much attention in the circles of power. Consequently, while the communist regime was running the pioneer camps based on military-like discipline, in the kingdom of Pipecland the subjects could continue their untroubled life.

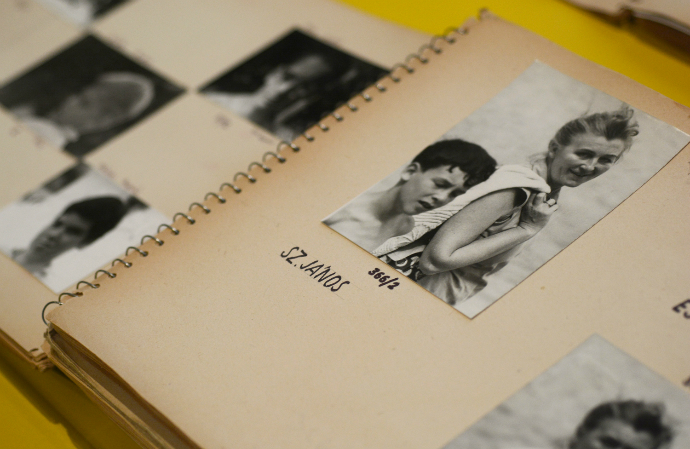

For a long time the Bánk community was only known in the participants’ circles. The Museum of Ethnography now set out to reveal the camp’s history and at some points it seems like a mission impossible: the interviewers, researchers and the curator had to open up a world tightly bound with very personal memories and emotions. Besides this, they had to show, through the figure of Eszter Leveleki, the link between the camp and the influences of other reform pedagogies in Hungary. Finally, they had to highlight the setting of a “state” which constantly and consistently defied the wider, parallel reality of Hungary, and still it was never banned. The curator, Zsófia Frazon, smartly turned upside down one of the principles of any exhibition: she reversed the ratio of the objects and the explanatory texts. Beyond the entrance the visitors find themselves among large walls fully covered with colourful texts. The objects and the pictures are – by their very nature – small, and are placed in vitrines in the middle of the rooms (the full English translation is available on separate sheets in each room). Nothing is enlarged in photos or into models, everything retained its real-life, personal, intimate character: the photo albums, the summer diaries, the hand-made board games, posters, knit-caps, flags and badges, the love/hate lists of food, the totem wall with ritual objects. Classifying would not have made much sense here. The text on the wall offer a retrospective analytical and interpretive view of the camp life, but the objects, pictures and documents keep their unique nature so much that the visitors feel like guests who can now hear these old stories, these decisive personal memories from the participants at first hand.

Was the camp a form of rebelling against the mainstream? No, most probably not. The only real rebel might have been Eszter Leveleki’s cousin, Gábor Molnár, called “Bear” in the camp. He took part in the street fights in the 1956 revolution in Budapest, immigrated to Switzerland after that, and kept in contact with the others from there. His memory pervaded the camps values, which is very smartly and sensitively depicted in one of the rooms, intelligently avoiding a myth creation. The rest of the participants were restrained to internal resistance and reasonable compromises in order to avoid dangerous situations in the hard and then later in the soft dictatorship of the 1950s and 1960s. The low key policy paid off surprisingly well: in the period following 1957, three top communists’ children and grand-children turned up in the camp.

Ms. Leveleki’s children paradise on earth offers us a great lesson on children, adults, trust and freedom. Even today’s mainstream pedagogy or parent-child relationship is very far from what this nursery school teacher achieved in Bánk during four decades. Some of the participants later founded and still run their own camps, but they can only realise some aspects of the original inspiring experience of freedom. True enough, times have changed.

The exhibition does not depict the camp as a utopia. It nicely emphasises the changes that took place during those forty years, it speaks openly and honestly about the controversies and – perhaps unintentionally – through its rigorous analysis it, actually, questions the viability of any successive camps. It evokes the camp experience, and beyond that, it tells us the story of how a community can, even under the most hopeless social and political circumstances, endeavour to teach children to soar and grow roots at the same time.

The exhibition is open until 30 August 2015.

Curator: Zsófia Frazon

Co-curators: Melinda Kovai, Eszter Neumann, Zsolt K. Horváth, András Vigvári, Margit Barna, Veronika Hermann

Exhibition design: David Karas

Typography and graphic design: Gábor Dávid

Photography: Krisztina Sarnyai