Works of Art

Is it possible to exhibit a war?

This is the sixth part of the series exploring the potentials, methods and tools of war exhibitions.

| Lakner Lajos |

2015-09-15 10:15 |

Works of art play a very important role in war exhibitions too. On the one hand they depict war events, on the other they trigger feelings in the visitors: What is fear like? What is it like to long for our loved ones? What is it like to tolerate pain, to accept the loss of our comrades or to face the approaching tanks from the trench? The former case is about depiction, the work of art mostly remains independent of the spectators, while in the latter case the work of art is actually realized and completed only by the active participation of the visitor.

The first case can be exemplified by Heinrich Hoerle’s Bildnis der unbekannten Prothesen which was put on display in the Wuppertal Museum’s Das Menschenschlachthaus, Der Erste Weltkrieg 1914 bis 1918 in der französischen und deutschen Kunst exhibition.

The picture shows three people. Two are seen from a side-view and they stretch their arms ending in prosthetics towards each other. Within the simplified head there are two black shapes. The first one resembles a skull, the other one is a gas mask, but the air filter is on the inner, brain side. In between the two, there is a third person largely resembling of a teddy bear, but still clearly human. His legs are amputated ending in disks similar to a buzz saw. One of his arms is missing, the other one is equipped with a knife like object, which can be a cutting tool or a prosthetic to replace the fingers. In the blue background the moon is shining. It is the only unimpaired, round object. The picture is a reference to the mutilation of the body and to its transformation into a machine. And also to the teddy bear-human’s vulnerability and how he becomes a toy. Wars make us machines and tools. This is why humans are victims of a war and not because they lose their limbs and become disabled. Looking at the picture, it is irrelevant what the spectator knows about the political and military facts of WWI. The work of art does not want to enrich the visitor’s historical knowledge, it wants to make the war and violence more understandable from a human perspective.

It is worth comparing this to two photographs depicting two soldiers.

One of them had lost his leg below the knee and is supporting himself with two sticks. The other one had lost both his legs. He could move around with the help of a rolling device. They look like as if they were smiling, but we cannot be certain because they are not looking into the camera. The photos remind the spectator that the war is essentially death, misery, suffering of families and crippling of lives. However, one has seen it so many times. News is pouring on us with the pictures of violence. Hoerle’s painting is much more complex and unsettling. It evokes individual fates but also evokes the mechanisms of power which turn humans into tools. While the photo does not force us to face the problem of being a tool ourselves, the painting does trigger this realisation. The photo opens up the past for a second, but then it closes it. The painting disregards the time. It poses the question here and now: do you want to be a tool?

The other type of works of art avoids depicting the objects, situations and human stories of a war. They place the emphasis on experience. Not artistic, but human experience. Its starting point is that the number of human reactions and sensual experiences are limited, in other words, the emotional and sensual reactions triggered by wars and violence can be triggered by other means too. An example of this is Tania Bruguers’ installation and performance. The visitors are walking in darkness and suddenly bright lights gleam straight into their eyes. In the darkness they were uncertain, but after a while their eyes got used to it, and when the bright light suddenly hit their eyes, perhaps it even hurt, while they heard the sound of boots stamping the ground and weapons clanking. All these were taken in by them as a form of violence. The artist assumed that the inability of orientation, the total uncertainty, and going through this mild form of violence would be stored as an intensive somatic experience in the participants’ memories. The visitors mostly produced two different reactions: some recoiled deeming ruthless and hardly bearable what they had just gone through, others interpreted their horror as a form of theatre.

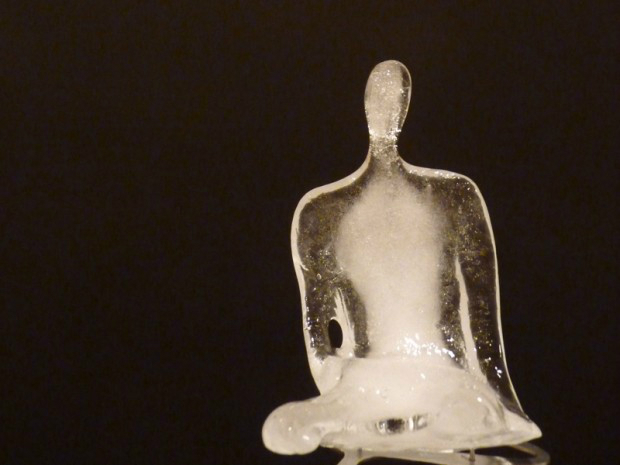

Another work of art involving the visitors is a tribute in several European cities to the civilian victims of the war. Five thousand faceless ice figures were slowly melting on the stairs of the square. They were waiting for decay which reached one sooner, the other one later. Nobody could tell who the next victim would be. Nele Azevedo, the Brazilian artist, wanted to remind us those “who monuments have rarely been erected to”. A further twist of the project is that all her helpers were unnamed volunteers. What is the message of the installation? Firstly, heroes are not only the famous heroes, but also the everyday people whose lives and deeds are not recorded in books or on films.