The Critique of Institutions and After

A Review of the Ludwig Museum’s Site Inspection - The Museum on the Museum

To commemorate the 20th anniversary of its first permanent exhibition, the Ludwig Museum has unveiled Site Inspection - The Museum on the Museum.

| Ivey Ford |

2011-08-20 09:00 |

|

Thomas Struth: Audience 1 (Galleria dell'Accademia),

Florenz, 2004 Photo © MUMOK,

Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien,

acquired with benefits of the MUMOK Board

|

To commemorate the 20th anniversary of its first permanent exhibition, the Ludwig Museum has unveiled Site Inspection - The Museum on the Museum. On view until October 23, 2011, the exhibition is comprised of several Hungarian and international neo-avant-garde artists and collectives whose aim is to question museums as institutions. Works in the exhibition respond to the categorization of art, proper museum behavior, interpretation of art, stolen art, art history, the hegemony of the West, feminist critiques, etc. This practice, known as institutional critique, began in the late 1960s and 1970s in North America and Europe and continues to be a topic of great debate in the contemporary dialogue. Site Inspection - The Museum on the Museum surveys the multiple trajectories of artists and collectives committed to institutional critique at the moment of its inception and how it continues to be a genre of interest with each succeeding generation of artists in an expanding art world. However, the history, contemporary state and criticisms of institutional critique still abound and deserve further analysis.

|

Marcel Duchamp: La Boîte-en-Valise, 1938-1941

Photo © MUMOK, Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien

|

Institutional critique began to take form from developments in Minimalism, conceptual art, formalist art criticism, appropriation art and structuralist and post-structuralist theories. First generation artists such as Hans Haacke, Daniel Buren, Marcel Broodthaers, Michael Asher and Mierle Laderman Ukeles made works that debunked the myth that culture is neutral and that the historical memory museums seek to preserve is anything but subjective. It was not until the 1980s that the term “institutional critique” was first used to describe such works, and it was not until an essay by Benjamin Buchloh published in the journal October in 1990 entitled “Conceptual Art 1962-1969: From the Aesthetic of Administration to the Critique of Institutions” that this practice became more defined. Buchloh discussed the importance of conceptual art in the context of Minimalism, aesthetics discourse and the relationship between art and the institution. Buchloh claimed with the onset of conceptual art and the dematerilization of the art object, the institution of art and the administration that supports it would have to revolutionize to adhere to these developments. The very nature of conceptual works led the way for a deconstruction of the art institution and a redefinition that became the focus of many artists working within models of institutional critique. The institution had to change to keep up with the art, but how and has it?

|

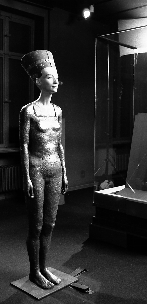

Little Warsaw:

The Body of Nefertiti

(After the unification

at the

Egyptian Museum

Berlin), 2003

Photo: Lenke Szilágyi

|

Today, nearly five decades after the first works criticizing the institution were created, there remains the obvious question, “were they successful?” The answer to such a question is not easily ascertained and continues to be a topic of current debate, but through the lens of the most recent contribution to that history, Site Inspection - The Museum on the Museum, the reiterated criticisms retain validity. The works are still displayed in the “white cube” of the institution and, at times, are overly complex. Also, many of the works in the exhibition are performance based, so in order to be exhibited, there must be some documentation rather in the form of photographs or videos. Which then is valid as the work of art, the performance that happened in the 1970s or the photographic evidence of that event? The final question remains, what criteria must artists meet to be canonized in a system that is under attack in their work? These are not new questions.

Despite these inherent criticisms, there are a number of works on display in Site Inspection - The Museum on the Museum that really operate outside of this institutional system and fully implement anti-authoritarian strategies. It is through the Ludwig’s careful selection of works, some of which are on view for the first time, which makes this exhibition so compelling. For example, Ulay’s (Frank Uwe Laysiepen) There is a Criminal Touch to Art (1976) provides new meaning on the topic of stolen art. In a thirty minute surveillance-like documentation, visitors watch news reports of the event with Ulay's description. In 1976, Ulay successfully stole Carl Spitzweg’s The Poor Poet (1836) from Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin. He then hung the painting in an immigrant Turkish family’s living room. After a couple of hours he called the Neue Nationalgalarie’s Director to invite him over and see the work. Shortly afterwards, Ulay was arrested and sentenced to a fine or imprisonment. The work is significant because Spitzweg was both Adolf Hitler’s favorite painter, and the painting served as a symbol for German national identity. These facts combined with the divide of Berlin during the Cold War and the poor treatment of West Berlin’s largest minority, the Turks, raise multiple meanings in this illegal act.

|

Dalibor Martinis: Art Guard, 1976

Courtesy of the artist

|

Another fascinating work on display is Lakner László’s Football in the Museum of Fine Arts, (1971). Lakner wrote a series of letters to Harold Szeemann, former director at Kassel, and requested an action where eleven Hungarian artists would play eleven international artists in a game of football in the Museum of Fine Art in Budapest. Although the work was never actualized in its original inception, there remains an art book, documentation and photographic evidence. The work comments on proper museum behavior and the place of Hungarian art on the international scale, but unlike a number of works in the exhibition that have the same focus, the significant point is that the institution of art would and could not accommodate it.

|

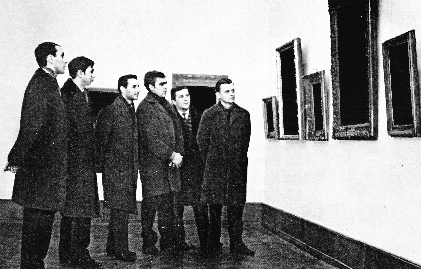

Endre Tot: Ein Besuch im Museum| Museum Visit, 1972

Courtesy of the artist

|

Although the exhibition displays significant works from the 1970s, there are more recent works that implement anti-authoritarian strategies as well. On display is a work by Ivan Moudov entitled Fragments box #5 (2002-2010). In this work, he collects small fragments of other artists’ works from around the world and neatly places them in a display box. Accompanying the box is a key that tells which pieces come from which works. For example, Moudov’s work has a small plastic flower from Claes Oldenburg’s Lingerie Counter (1961) from his workshop in New York’s Lower East Side known as The Store. Like Duchamp's Boîte-en-valise, or box in a suitcase that is also on view at the Ludwig Museum, the work serves as a sort of traveling museum of stolen objects. However, this work updates Duchamp’s ideas of the readymade in that it also comments on the illegality debate in appropriated works.

The complexities of institutional critique continue to challenge the contemporary art world, but the latest contribution to that dialogue, Site Inspection - The Museum on the Museum, demonstrates that this practice shows no signs of slowing down or giving up. Works from this exhibition confirm that art and the institution are not timeless domains, and they deserve redefinition over space and time.

Artists in the exhibition include

Richard Artschwager, Azorro Group, Birkás Ákos, Olga Chernysheva, Hubert Czerepok, Mark Dion, Marcel Duchamp, Henry Flynt, Andrea Fraser, Hans Haacke, Halász Károly, Kele Judit, Kis Varsó/Little Warsaw, Kostil Danila, Oleg Kulik, Lakner László, Marysia Lewandowska, Dalibor Martinis, Menesi Attila, Ivan Moudov, NETRAF, Pauer Gyula, Allan Sekula, Kalin Serapionov, Sean Snyder, Nedko Solakov, Thomas Struth, Téreltérítés Munkacsoport, TNPU / IPUT (St.Turba Tamás), Tót Endre, Ulay

Curated by Katalin Székely with the Ludwig Museum’s curatorial collective (Barnabás Bencsik, Nikolett Erőss, Kati Simon, Krisztina Szipőcs, Hedvig Turai).