Exploring issues

INTERVIEW

Although the exhibition Art and Artists in the First World War has been closed now, it raised so many fascinating questions that we turned to Enikő Róka, one of the curators, to discuss some of them.

| Berényi Marianna |

2015-01-21 11:38 |

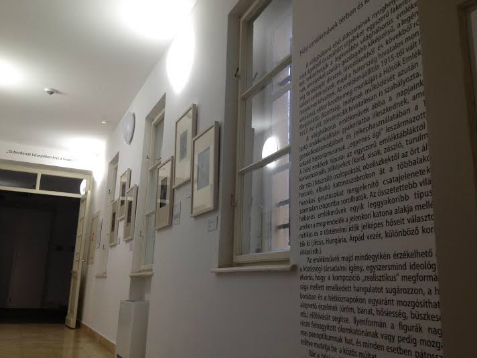

Considering the holocaust interpretations in museums Hedvig Turai has recently posed the question: “Does artistic representation have anything to do with historical museums?” The same issue was placed into the focus of the Art and Artists in the First World War exhibition in the Vaszary Gallery in Balatonfüred. The exhibition featured approximately 150 works of art selected from the collection of the National Gallery and was meant to be the forerunner of a larger exhibition in the National Gallery in 2018. The curators Enikő Róka, György Szücs és Eszter Balázs aimed to direct the attention on the relationship between art, war propaganda, the society and the career of individual artists as well as to revisit the collections of the National Gallery and to bring marginalised topics into the centre of attention. The works of art which finally comprised the exhibition were not selected exclusively on the basis of their aesthetic value. High artistic quality as well as popular pictorial products of the era was treated as imprints of the visual culture of the post-WWI period and as something with the help of which a more colourful picture might be created about the war as a historical event.

Considering the holocaust interpretations in museums Hedvig Turai has recently posed the question: “Does artistic representation have anything to do with historical museums?” The same issue was placed into the focus of the Art and Artists in the First World War exhibition in the Vaszary Gallery in Balatonfüred. The exhibition featured approximately 150 works of art selected from the collection of the National Gallery and was meant to be the forerunner of a larger exhibition in the National Gallery in 2018. The curators Enikő Róka, György Szücs és Eszter Balázs aimed to direct the attention on the relationship between art, war propaganda, the society and the career of individual artists as well as to revisit the collections of the National Gallery and to bring marginalised topics into the centre of attention. The works of art which finally comprised the exhibition were not selected exclusively on the basis of their aesthetic value. High artistic quality as well as popular pictorial products of the era was treated as imprints of the visual culture of the post-WWI period and as something with the help of which a more colourful picture might be created about the war as a historical event.

MMO: The exhibition’s motto was a Hayden White quote: on “the common constructivist character of both artistic and scientific statements". How does the author of The Burden of History and The Historical Text as Literary Artefact become a basic source of influence for an art history exhibition?

Enikő Róka: Hayden White’s works did not only influence historians, but his statements offer plenty to think about to museologists too. White’s basic point is that writing history essentially has a type of fictional character, and historians select the facts and then, following some rules borrowed from literature, they turn these facts into a narrative. This description is basically true for museum exhibitions too. The historian – along the scientific and methodological consensus of his era – links his data to his own present and transforms them into a subjective narrative. The curator in the museum virtually does the same: selects from a group of objects, interprets them and by installing them creates a coherent, but guided narrative in line with the curatorial intentions. According to White, there isn’t a single correct view, and consequently there might be several narratives and we can depict a topic at an exhibition in several different ways. One of the starting points of this exhibition in Balatonfüred was that we wanted to offer only one possible interpretation of this vast and complex material, which is historical and art historical at the same time. The aim was to call the visitors’ attention to the fact that more than one interpretation of a historical event is possible and acceptable. Hence we began the exhibition with the present by exhibiting contemporary works of art which, in different manners, reflect on wars and history in general. Obviously, artistic interpretation is not equivalent to that of the historians. The former can handle facts more freely and, by this, it can offer such approaches which can impregnate the interpretation of historical events and of the present too. The first room with the often ironic contemporary works of art enabled the visitors to consciously think about their positions and to distance themselves from what they would see in the rest of the exhibition. This way they were offered a critical position from which they could contemplate the sometimes tragic, heroic or pathetic works and could rethink the era which imposed mechanisms of propaganda expectations, control and self-control on the artists. This hopefully led the visitors to a critical thinking on WWI and also on the present.

MMO: Departing from the present, how many times did the visitors have to change their perspectives?

MMO: Departing from the present, how many times did the visitors have to change their perspectives?

Enikő Róka: The contemporary section featured a work by Société Realist (Ferenc Gróf and Jean-Baptiste Naudy) titled Spectral Aerosion which pointed out the differences between points of view. It was a one square-metre Perspex sheet with the map of Europe on it featuring the borders between different countries in the last 2000 years. It is practically a fuzzy network of lines, ironically questioning the idea of nation states: in an exhibition on the First World War this brought some absurdity into the interpretation of these borders, since the war was fought partly for theses very borders. Seeing it from this angle, nothing could be taken for granted and everything was open to doubt in the exhibition which followed a reverse chronological order.

MMO: The next part of the exhibition featured photos and plans of monuments evoking the politics of remembrance of those generations which went through the ordeal and the trauma of the First World War. The style and ornaments of the monuments erected right after the war and between the two world wars repeated the supposedly ancient symbols and 19th century clichés talking to the audience in a way full of pathos. This symbolising and visual strategy appeared in the exhibition as a pictorial language tied to historical contexts and specific aims.

Enikő Róka: It was after these heroising and pathetic monuments when the visitors arrived at the time of the war. Many topics appeared in the works of the artists who experienced the hardships of the war: the occupation, the “mutilation of nature”, the “dumb battle fields”, the funerals. However, before the spectators could immerse themselves in the images of the war, the wall texts warned them: beyond the primary events and spectacle, the works were defined by their context, expectations, aims, functions and by politics. In other words the artists could not see everything, and could not let everything be seen. For example, those who worked at the press headquarters had to meet certain expectations while among those fighting on the fronts strong self-censorship was common. The exhibited works – independent of their aesthetic qualities – offered a picture of the war which was construed and influenced by several factors.

In the last room of the exhibition images of the hinterland were on display. They were images either for or of the hinterland. The press headquarters’ exhibitions offered different genres: soldier portraits, emotional genre scenes of the soldiers’ homecoming, all of which were aimed to arouse compassion in the hinterland. The posters which encouraged the people to help the disabled and the war orphans were either heroic or satirical. Posters, by definition, do not document, but call and direct the attention and do not go into detail, but places something into the focus. It mobilises, informs and sometimes – though in the case of the Hungarian collection it is rare – it creates a scornful enemy image. Besides the directly propagandistic posters, commercial posters also appeared in the exhibition along with some images of the cinema which became extremely popular during the war.

In the last room of the exhibition images of the hinterland were on display. They were images either for or of the hinterland. The press headquarters’ exhibitions offered different genres: soldier portraits, emotional genre scenes of the soldiers’ homecoming, all of which were aimed to arouse compassion in the hinterland. The posters which encouraged the people to help the disabled and the war orphans were either heroic or satirical. Posters, by definition, do not document, but call and direct the attention and do not go into detail, but places something into the focus. It mobilises, informs and sometimes – though in the case of the Hungarian collection it is rare – it creates a scornful enemy image. Besides the directly propagandistic posters, commercial posters also appeared in the exhibition along with some images of the cinema which became extremely popular during the war.

MMO: Did anything surprise you while you were looking for the imprints of WWI in the collection?

Enikő Róka: Well, the exhibition space in this museum in Balatonfüred is much smaller than those of the large museums in Budapest. Consequently from the beginning we were planning an exhibition that can raise issues instead of giving a comprehensive overview. And indeed during our research in the storage rooms we came across a lot of graphics, sculptures and paintings from artists like Ferenc Márton or Mihály Bíró. The works we chose from them were novelty for art historians too.

MMO: How much time did it take to curate this exhibition?

Enikő Róka: It is not easy to say the exact time. All of us, György Szűcs, who was the co-curator and Eszter Balázs, our historian, and myself have been doing research in this field for a long time. So, we had a certain basis on which we could build when we started this project. For selecting the works, elaborating the concept, implementing the exhibition and compiling the catalogue we had six months.