From the Székely Gate to the Last Towel

EXHIBITION

In terms of its topic it is ambitious, in terms of implementation it is fastidious although its title is far from reflecting all these values. An exhibition in the Museum of Ethnography in Budapest.

| Keszeg Anna |

2015-10-20 10:58 |

From the Székely Gate to the Last Towel: the rather encyclopaedic sounding title refers to the complexity that characterises the exhibition: it depicts the daily routine of a ethnographical collecting tradition, its objects and its methods, it also refers to the exhibition’s great design while dispelling some misunderstandings which originate from the quest for archetypes. Perhaps the title should have dropped a hint that what is primarily happening here is that the Museum, as a place of scientific research, is clarifying some misunderstandings related to ethnographic objects.

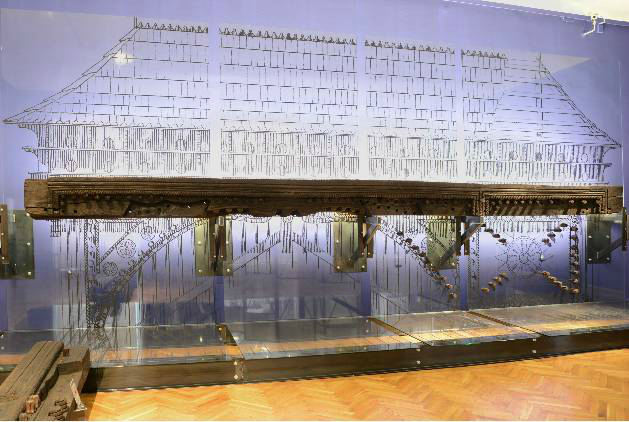

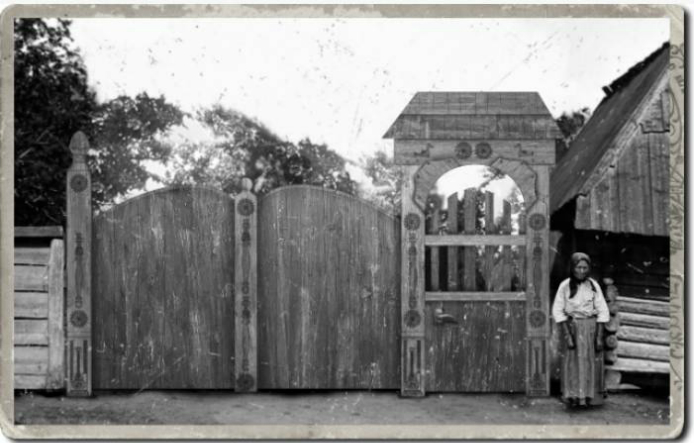

The three rooms of the exhibition reconstruct the work of a collector, the first one offering a well documented biography of Gábor Szinte, the other two highlighting two of the most important elements of Szinte’s work: the székely gate and the székely house. The visual design by Beatrix Kiss is largely built around these, and her inclination to use theatrical elements in the design is as fascinating as spectacular.

Two colours dominate the exhibition, the blue and the brown, the former making the all two often used chromatic scale of the latter more dynamic and helps join smoothly the different materials like wood, plastic and paper in the exhibition. Sophisticated visual ideas characterise the multimedia installations too, which were produced in collaboration with the MOME Techlab.

One of the exhibition’s merits is documenting the collection technique Gábor Szinte used. The first room helps to answer the question: what were all those museum people like who amassed our public collections with their often passionate work? This time the focus is not on the wealthy nobles or upper-class entrepreneurs whose passion for different species of objects manifested itself in diverse collections, but it is about the quiet, and for the public, almost invisible museum professionals, who often carried their technical equipment on their back to their fieldwork. The curators call Szinte a “drawing teacher”. This puritan, perhaps slightly downgrading adjective reflects an attempt to restore the more prestigious early twentieth century meaning of the word. The other term used to describe Szinte is the “fieldworker”, which, in Hungarian, was originally used for the people who were employed by the museums to record and document rural folk culture. It draws the attention to the contemporaneous practice of doing fieldwork with a degree in artistic drawing and being commissioned by a museum. Gábor Szinte, who was born in Sepsikőröspatak, Transylvania, obtained a drawing teacher degree in the Országos Mintarajztanoda (the predecessor of the Budapest University of Fine Arts) and used his expertise he learnt there during his fieldworks. The first room places emphasis on the Mintarajztanoda and the techniques and methods taught there and these methods also serve as titles for the different sections of the exhibition.

The curators wanted to set up a genealogy of these teacher-fieldworkers’ expertise. This is reflected by the title “The documentation as heritage” under which several sub sections bear titles like “Details and tracing paper – the wall picture”, “Plan and photo – the székely house” “Pairs of compasses and rulers – the székely gate”, “Wooden model and scale - the wooden headstone” “Glass plate negative and structural plan – the wooden church”. This time the curators do not want to talk about the observers, but about the observers’ methods and how these methods generated knowledge. Gábor Szintes’ photos and drawings systematically revealed the patterns and structures of the wooden head stones, gates, houses and churches in Transylvania. In this case the descriptions of a large number of individual instances were preferred to ambitious, however less factual, descriptions based on few examples. With the help of this it became possible to shed light on the choice of patterns on the wooden headstones: it rather depended on the local carpenter’s abilities and technical skills than on some previously supposed archetypical symbolism.

The leaflets and the catalogue also steadily support the exhibition, however the QR code based application feels sometimes slightly confusing. Having said that, the székely kapu design app (made by the P92rdi Informatikai Szolgáltató Kft.) is brilliant and highly amusing.

From the Székely Gate to the Last Towel. The collections of Gábor Szinte

Museum of Ethnography

Curators: Tímea Bata – Zsuzsanna Tasnádi

Photo: Krisztina Sarnyai, Eszter Kerék