Mapplethorpe at the Ludwig

Currently on view at the Ludwig Museum is a large-scale collection of renowned American photographer Robert Mapplethorpe (1946-1989).

| Ivey Ford |

2012-06-21 14:10 |

|

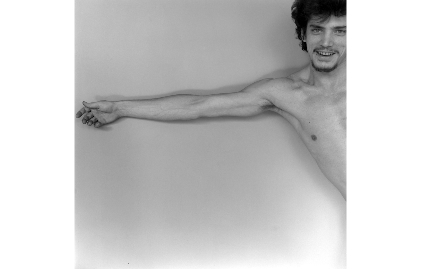

| Robert Mapplethorpe: Self Portrait, 1975 |

Shock and controversy have always been mainstays in the history of art, and with this provocation, there often arises the delicate line of censorship. With time, the once avant-garde work is consumed and the mainstream selectively digests to the canon of art history. What remains the same is the art, and it is the world that often changes. Currently on view at the Ludwig Museum is a large-scale collection of renowned American photographer Robert Mapplethorpe (1946-1989). In the late 1980s and the 1990s, his work became the target for the cultural-political debates in the United States known as the Culture Wars. Shortly after his death, his works became the center of controversy leading to the loss of artistic funding, a cancelled exhibition, an arrested curator and the eventual reexamination of government support for the arts in general. Today, over twenty years after Mapplethorpe’s death, nearly 200 of his photographs are on display featuring his most beloved subjects: celebrity portraits, still lifes of flowers and food, self-portraits and the nude. It is the explicit homoerotic and sadomasochistic themes surrounding primarily his male nude photographs that have always spearheaded the debate. However, what connects Mapplethorpe’s subjects is their momentary, sensual objectivity and what makes them controversial is often the subjectivity of the viewer or political platforms. Although the controversy concerning Mapplethorpe’s imagery may have subsided in the past 20 years to some degree, very current questions remain: should tax dollars support the arts, is art protected under the United States’ First Amendment of free speech and who has the authority to determine if an artwork is “obscene”? And finally, how is Mapplethorpe’s work viewed in a Hungarian context?

|

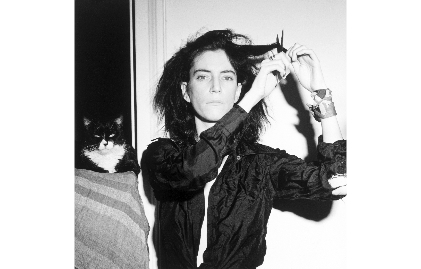

| Robert Mapplethorpe: Patti Smith, 1978 |

Born and raised in Queens, New York in a large Catholic family, Robert Mapplethorpe attended the esteemed Pratt Institute in Brooklyn and studied painting, drawing and sculpture. His devout religious beginnings permeated his artistic career in terms of composition and form. In 1967, he began a first romantic and then friendly relationship with famed musician Patti Smith which continued until his death. In 1969, he dropped out of college, and in the 1970s began taking photographs of friends and people he knew with first a Polaroid camera and soon after with a Hasselblad medium-format camera. He had his first solo exhibition at New York’s Light Gallery in 1976 which included Polaroid photographs of flowers, portraits and erotic images. Early on, he gained a notorious reputation for his explicit representation of Manhattan’s gay community, particularly in works focusing on BDSM. It was during this time that he created his infamous X Portfolio series which came under national attack in the 1990s. By the 1980s, he had refined his aesthetic to include flowers, food and the nude, particularly the male nude. It was also during this period that Mapplethorpe’s mentor and close companion Sam Wagstaff became his benefactor and helped further define the importance of photography as a medium of fine art. Robert Mapplethorpe died from complications of AIDS in 1989 at the age of 42. Before his death, he helped found the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, Inc. Today, the Foundation owns Mapplethorpe’s estate, and it is committed to internationally exhibiting his work and raising money for the fight against HIV and AIDS.

The controversy surrounding Mapplethorpe’s work climaxed in the summer of 1989 when a U.S. travelling solo exhibition entitled Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Moment was to come to the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. The exhibition was curated by Janet Kardon of the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) and was not met with controversy in all exhibition venues. However, many people at the Corcoran and several members of the U.S. Congress found the exhibition too “obscene” and “indecent” for exhibition. Religious and conservative groups, such as the American Family Association were infuriated that the National Endowment for the Arts, an independent agency of the United States federal government that financially supports the arts in the U.S., had helped support the exhibition. In addition, it is important to note that many of these attacks and grants occurred posthumously. After much debate, the Corcoran declined, and the exhibition was held by the Washington Project for the Arts, where it was highly viewed. The following year, the Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati held the exhibition, and the curator, Dennis Barrie, was arrested and unsuccessfully prosecuted. In 1998, British police confiscated a book of Mapplethorpe’s photographs entitled Mapplethorpe from a final year undergraduate student from the University of Central England who wanted to include some of the images in her final paper. In 2000 in South Australia, Mapplethorpe’s monograph entitled Pictures was confiscated by two detectives in an Adelaide bookshop for breaching presumed obscenity laws. In all cases, charges were dropped and books were returned, but Mapplethorpe has come to epitomize the contemporary debate over censorship at both ends of the spectrum.

Do these claims still have validity in 2012? How is obscenity defined and who determines it? And to what degree is the debate over what content can and cannot be shown in an exhibition eventually a subjective endeavor that hinges on religious belief or a clear definition of art? And finally, are Mapplethorpe’s works still controversial or has controversy preceded his legacy?

|

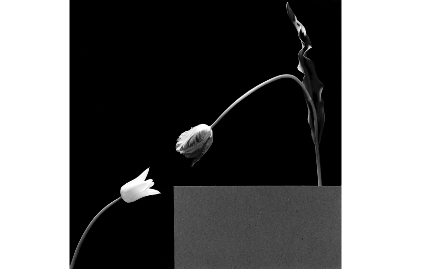

| Robert Mapplethorpe: Two Tulips, 1984 |

The Ludwig’s exhibition displays three films and nearly 200 photographs with a survey of works throughout Mapplethorpe’s life. The exhibition is grouped thematically according to subject. No matter what his subject is Mapplethorpe strives for the same flawless moment in time or the “perfect moment” and one that is wholly understood within its frame. Like the photographers Edward Weston and Nadar who Mapplethorpe pays homage to, the works leave the viewer with no questions– all is given to us. In an interview with curator Janet Kardon in 1988, Robert Mapplethorpe stated, “I just would like people to be able to get the real meaning.” He explains how his later works are meant to be shown together as it does not matter what the subject is but rather the overall context of how the works are shown together. He also states in the same interview, “I don’t think I see differently just because the subject changes.” His aesthetic seeks beauty through rigorous duty to formalism–heavy contrast, close details without abstraction, clean lines and intriguing compositions. Simultaneously, he explores issues of sexuality, religion, fame, disease, gender, body, taboo and androgyny. His work both positions in the history of art formally and retains its significance today for seeking a broader definition of art.

The exhibition opens with portraits of celebrities, artists, friends, film stars and musicians. Mapplethorpe’s portraits have an uncanny ability to express the personality of the sitter. Perhaps it is the obvious trust between the sitter and Mapplethorpe or the instantaneity of photography to capture the “perfect moment” that makes the works so aesthetically captivating. For example, his portrait of Andy Warhol from 1986 is a close-up view of Warhol looking directly into the camera. Through careful formal arrangement, we see not the immortal Warhol as he was known and often depicted, but rather the humility and apprehension of a man a year before his death. Warhol dominated the art world during Mapplethorpe’s life, and Mapplethorpe pays homage to his legacy while at the same time breaking the mirage of fame and celebrity in the process.

In addition to portraits, Mapplethorpe also took a number of self-portraits. They range from Self-Portrait (1980), where Mapplethorpe is clad in make-up and fur à la Marcel Duchamp’s Rrose Sélavy to Self-Portrait (1980), where Mapplethorpe is wearing a black leather jacket with a cigarette dangling from his lips, reminiscent of James Dean. The exhibited self-portraits also include one of the central photographs under attack in the Culture Wars entitled Self-Portrait (1978). In this self-portrait, Mapplethorpe is dressed in leather and has a bull whip inserted in his anus. His expression is not one of confidence but one of apprehension and/or surprise. Whatever scene he creates, it becomes apparent that Mapplethorpe’s careful capturing of the “perfect moment” in others was not always the case for him. With every self-portrait on view, the viewer sees his endless search for an identity that was quite topical and always in a state of flux. However, it is certain that through these images we see a man from his own perspective battling AIDS on film over time. By turning the camera onto the site of his own body, Mapplethorpe broadened the definition of photography and its medium specificity to consider issues of time, vulnerability, disease, identity and/or body–issues which continue to permeate the contemporary art world today.

|

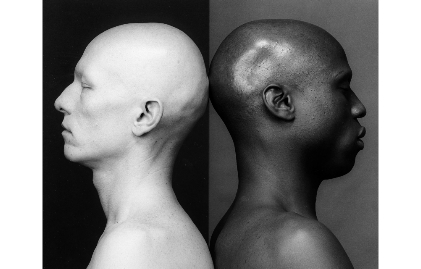

| Robert Mapplethorpe: Ken Moody and Robert Sherman, 1984 |

Included with the analysis of portraits is also Mapplethorpe’s focus on the human form. Perhaps his most notably controversial subject matter, Mapplethorpe photographed mainly male but also female bodies and nude statues. His focus on the body ranges from close-up views, such as the hands, to the nude body as a whole, thus signaling a constant gestalt. His black and white aesthetic is further explored through his contrast of the medium with the skin tone of the subjects, such as his work Ken Moody & Robert Sherman (1984) which contrasts African American and Caucasian skin. The works are certainly a continuation of the study of the male nude that was of interest in the Renaissance and Mannerism, but Mapplethorpe contributes to this history by focusing on the African or African American male body. Artists have a tendency to create what they do not see in the world, so Mapplethorpe began to focus on what was not already in the history of art–fetishsized images of the male African and African American body. True, his focus on the nude led to harsh criticism as to whether or not they are a form of exploitation, but in context to the other works, these claims remain questionable. In all of his works, there is a sense of voyeurism, but it is through Mapplethorpe’s gaze to capture the aesthetic beauty of form. Mapplethorpe directs both a careful planning of composition and form as well as how to view the work aesthetically.

Another subject of interest for Mapplethorpe’s camera is flowers and food. The posed still lifes evoke Edward Weston’s photography formally but are perhaps the most sensual of all. The passing of time and emotions like love and desire are elicited in the same manner as his portraits and nude studies. For example, the work Two Tulips (1984) expresses a longing for love that might as well be Adam and God’s fingers touching in The Creation of Adam from the Sistine Chapel. The choice of calla lilies, orchids and tulips are sometimes reference for human genitalia. Calla lilies become a symbol of androgyny as the series unveil. In one view, it serves as a metaphor for the lines of the female form, and in another, the petals and stamen serve as a phallus. With metaphor, his work breaks down dualities and opens a dialogue towards equality and beauty.

Overall, the exhibition provides an excellent oeuvre of Mapplethorpe’s work, and it is the first large-scale exhibition of Mapplethorpe’s work in Hungary. His work evokes discussions often taboo in Hungary, such as homosexuality, AIDS, racism, androgyny and/ or fetish. At the same time, questions over artistic freedom, display, censorship and/ or the politics of art are all present. Parental advisory is suggested for minors, but the exhibition is a “must see” for the summer.

Curator: ERŐSS Nikolett

The exhibition is accompanied by the catalogue, Robert Mapplethorpe. Photographs published by C/O Berlin, in 2011, which includes 138 reproductions of the works in the exhibition and is available at the museum shop on the third floor. English and German, 228 pages.

The exhibition is realized through collaboration with the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation New York.